Update: Court verdict for Shamila and Her Attackers

25/09/2018

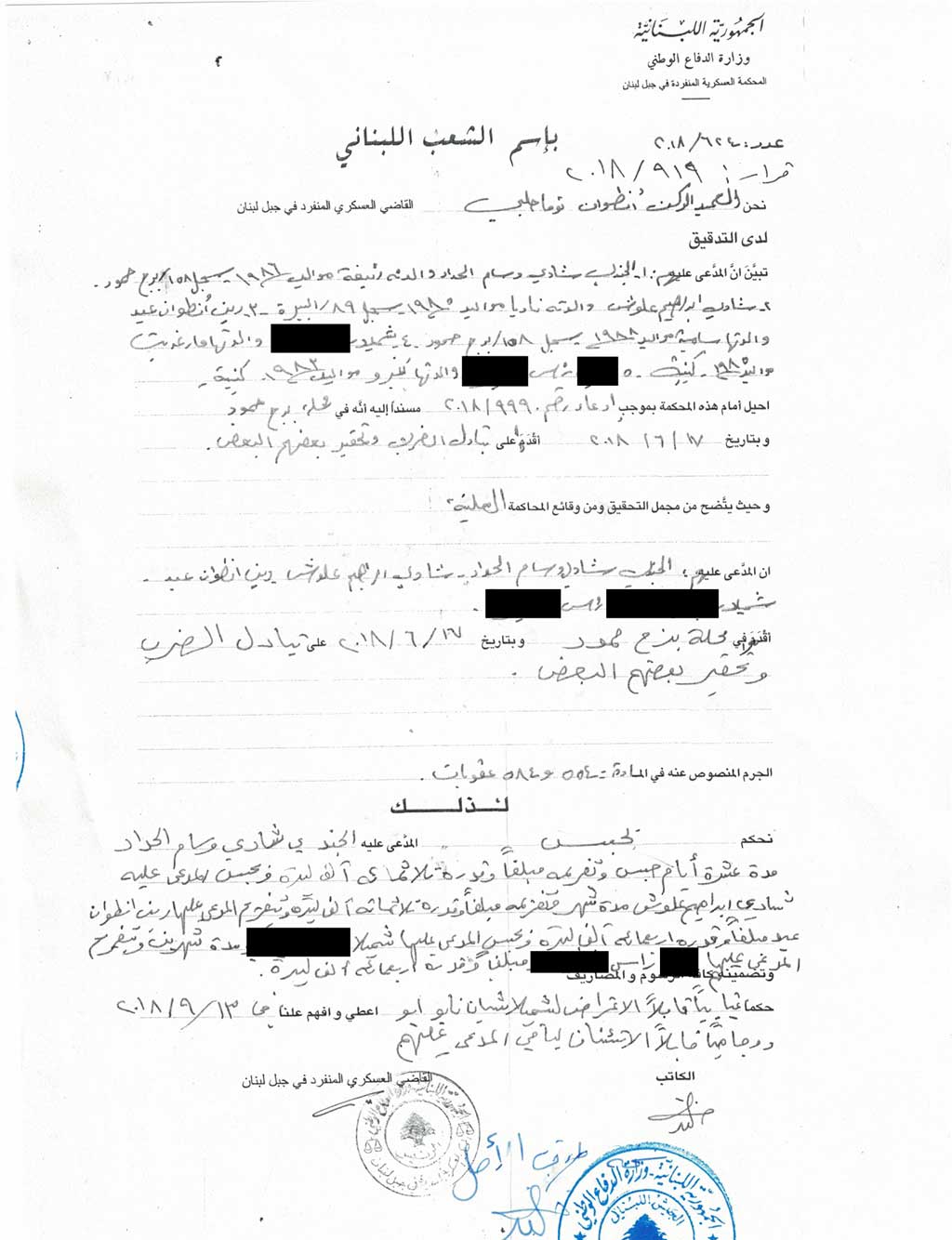

On September 13, the military court issued its verdict in the assault case of Kenyan migrant workers Shamila and Rose, and three of their attackers, two Lebanese men and one Lebanese woman.

Shamila and Rose were violently assaulted by a mob in Bourj Hammoud on June 17, 2018, and both prosecuted along with their attackers. Shamila was deported on July 15, despite legal action, public outcry, and media attention. The military court sentenced the two male attackers to jail time, fined all three attackers in addition to Rose, and sentenced Shamila in absentia to two months jail time, as she was not present to defend herself.

While the verdict is far from perfect, it sets an important precedent: migrant workers in Lebanon can hold their attackers responsible before the courts. At the same time, the verdict also demonstrates the limits on access to justice for migrant workers, caused by General Security practices and the decision to prosecute Shamila and Rose before the military court.

The Verdict: Access to Imperfect Justice

The court detained, imprisoned, and fined three of Rose and Shamila’s attackers, holding them accountable for the assault:

The first Lebanese man received one month of jail time and a 300,000 LL fine.

The second Lebanese man received 10 days of jail time and a 300,000 LL fine.

The Lebanese woman received no jail time and a 400,000 LL fine.

However, the court also penalized Rose and Shamila, reflect problems at several levels:

Rose received no jail time and a 400,000 LL fine. This reflects the court’s consideration that Shamila and Rose were participants in the fight, rather than mere victims of an assault, as this video of the attack shows.

Shamila was sentenced to two months jail time in absentia. This is a results of two main issues: (1) Shamila’s deportation by General Security and (2) the exceptional procedures at the military court, where Shamila was not allowed to defend herself through a lawyer, though prosecution was for an offense of less than a year (unlike the procedures in the ordinary courts). Shamila thus received the harshest judicial penalty of all five people.

This emphasizes the unfairness of prosecuting civilians in military court.

There is a 15-day period to appeal, so it is possible these sentences could change.

General Security Denied Shamila Her Right to Defend Herself:

General Security deported Shamila two months before the court proceedings finished and the verdict was released, depriving her of the right to defend herself. Shamila’s penalty could be vacated if Shamila returns to Lebanon and appears before the military court — but she cannot do this as General Security permanently banned her from returning to the country.

These practices demonstrate the complete impunity of General Security. By criminalizing, detaining, and deporting migrant workers without legal residency, General Security concretely deprives them of their basic human rights under international law.

The Limits of Justice in the Military Courts:

Prosecution in the military court severely restricted access to justice for Shamila and Rose in three ways:

Shamila and Rose’s lawyer Nermine Sibai repeatedly argued that this crime was a collective assault with bias motives, and that other identified perpetrators should be included in the prosecution. She asked for a minimum of three years of jail time for the attackers. The court dismissed this point and ultimately did not charge additional attackers .This reflects the military court’s focus on expedited verdicts, which hinders thorough investigation and ultimately produces unfair trials.

The structure and rules of military court do not allow Shamila and Rose to file a lawsuit and hence ask for compensation for the harm they suffered

The military court doesn’t have an obligation to explain its decision or back it with any reasoning, which deprived the persecuted women of understanding how responsibilities were distributed, on what basis, and why the final verdict charged them as well. This restricts arguments to appeal the verdict.

In Conclusion:

Although the sentence given was less than what Rose and Shamila’s lawyer argued for, the verdict still indicates that the judge accepted Rose defence and the culpability of the attackers. This ruling provides both important precedent to migrant workers seeking access to justice, but also reflects the limits imposed by General Security and the military courts, and practices which allow violence against migrant women to continue.

Shamila and Rose’s experience of violence on the street, by General Security, and in the courts echoes the experiences of 250,000+ migrant workers in Lebanon. Only weeks after their assault, for example, an Ethiopian woman was violently beaten outside a salon on the street in Bourj Hammoud — but the viral video resulted in no public outcry and no justice.

What about the thousands of cases without video evidence? We need collective effort to expand access to justice for these women, build on court precedents like that of Rose, and establish fair, humane legal and migration systems respecting the basic human rights for all migrant workers.

For more info on the case, see our statement on Shamila’s deportation here, the initial video of the assault here.

Have Any Questions?

To inquire about this statement and the context, email us or fill the form.

Join Our Newsletter

At the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM), we are constantly working on a multitude of different activities and initiatives. Most of our activities are only possible with the help of dedicated and passionate volunteers who work in collaboration with our core team.

The Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) was launched in 2010 as a grassroots collective by young Lebanese feminist activists in collaboration with migrant workers and migrant domestic workers.

Quick Links

Useful Links

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Developed by CONCAT