Migrant Deaths in Lebanon: Concealed Causes | News Report: September 2023

18/10/2023

Migrant deaths in Lebanon are often hidden behind incomplete reporting or blocked investigations. Thus, seeking justice becomes a struggle. Here’s our news roundup report for September 2023, compiling news about migrants and refugees in Lebanon, and the region.

Articles and views shared in the News Report do not necessarily represent ARM’s views. Information in these articles has not been fact-checked by ARM and may contain some errors. ARM is simply compiling all news relevant to migrant communities to inform our advocacy efforts and to facilitate the work of organizations that cater to migrant communities.

H. Kh, a Syrian worker, died from an electric shock while cleaning a store in the town of Beddaoui, near Tripoli.

The worker was hospitalized at the Islamic Charity Hospital, but she, unfortunately, did not survive the injuries from the shock.

An Ethiopian worker was hospitalized in Tripoli after falling from an employer’s balcony, which injured her severely. Her state was described as “unstable.”

Lebanon24 reported that the worker was fleeing her employer’s house, without mention of the employer’s treatment or the environment of the workplace.

Authorities released M.Q.H, an employer suspected of the murder of Mulu Mikasha Nagasi, aged 35, through a bail of 200 million Lebanese pounds (equivalent to roughly 2,000 US dollars, as per the time of reporting).

Nagasi’s body was repatriated to Ethiopia in July through the Ethiopian embassy, with the employer having paid around 2,500-3,000 USD to the company responsible for the repatriation of the body, in addition to medical bills following her death, and 17 months of unpaid salary from February 2022 until July 2023 (150 USD per month, total of 2550 USD).

Bekaa’s Public Prosecutor, Judge Munif Barakat, had already arrested the employer during an investigation into her murder, a crime punishable by a prison sentence of over five years with hard labor, under Article 550 of the penal code. The public prosecution based their accusation of manslaughter on acts of violence and medical neglect.

Barakat pled the release order five times, but Judge Hares Elias of the Indictment body in Bekaa rejected the fifth plea, which led to the employer’s release.

According to Legal Agenda’s sources, the case is still ongoing and awaits the response of the Ministry of Justice, which is investigating the forensic doctor who examined Nagasi’s body.

Barakat accused the doctor of falsifying testimonies. The doctor is suspected of omitting the reference to bruises and scratches on the body. Falsifying testimonies is a crime punishable by a prison sentence between two months to two years, according to Article 466 of the penal code.

Barakat’s arrest of the employer sets a precedent when investigating the death of migrant domestic workers, which is often either passed off as “suicide” or does not receive proper investigation, especially if there is no clear or direct evidence of violence.

Mouhanna Isaac, a lawyer from Kafa, stated that the employer had confiscated Nagasi’s wage for two whole years, before February 2022.

Kafa had already been aware of Nagasi’s case and informed the General Security (GS), who brought the employer into questioning, and arranged for Nagasi to meet with a social worker.

The employer reached a settlement with the GS to pay for one out of two years’ worth of salaries, promising to pay the remaining salaries in installments.

However, the employer only delivered on this promise after Nagasi’s death. According to Isaac, the Ethiopian embassy signed a pledge to transfer the accumulated unpaid salaries totaling 1800 USD (equivalent to 12 months) to Nagasi’s family, which the employer reportedly paid to the embassy.

The amount of evidence against the employer is staggering: Not only was Nagasi denied medical care needed for her condition, but she was physically tortured, neglected and robbed of her salary for 29 months, and likely forcibly confined for 7 years, according to testifying neighbors.

Comprehensive Report on Domestic Workers Facing Torture and Sexual Abuse in the Gulf [here]

Raseef22 published a comprehensive article documenting the violence that migrant domestic workers face in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, all of which are countries that actively recruit domestic workers under the Kafala system.

The article details a long list of violations including torture, forced confinement, and wage theft, as well as sexual and psychological abuse.

The report, which was done in collaboration with various organizations, such as the Bangladeshi organization OKUP, Migrant-Rights.org, and SDDirect, highlights often-unreported insight into the reality of workers. Here’s a brief summary:

- The Nepalese Embassy in Kuwait receives over 30 cases of abuse weekly;

- On average, around 30 women are “snuck” outside of the employer’s house to the Nepalese Embassy in Riyadh monthly;

- The majority of complaints in 2018 were made by migrant workers from the Philippines in Saudi Arabia, followed by UAE and Kuwait;

- The Ethiopian Consulate in Dubai receives 5-10 complaints from migrant workers daily.

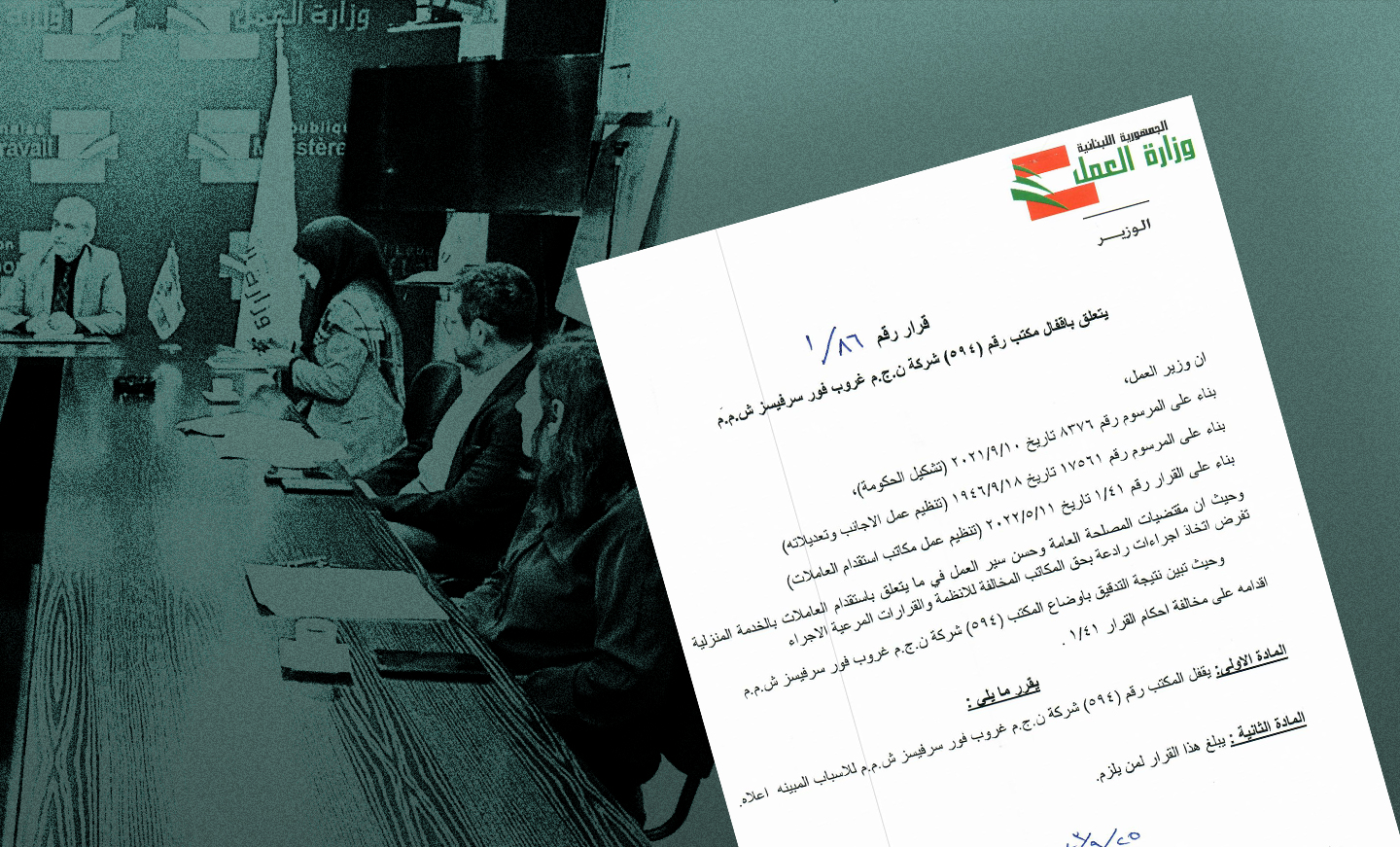

The Minister of Labor in the caretaker government, Moustafa Bayram, issued a decision to close two offices for recruiting domestic workers, as they violated laws, regulations, and valid procedures.

This comes within the framework of regulating recruitment agencies that employ practices akin to human trafficking.

Bayram also met with a committee from the International Labor Organization (ILO) to discuss informal labor and regularizing irregular workers.

The meeting was in the framework of a project titled “The Social Dialogue for Formalization and Employability in the Southern Neighbourhood (SOLIFEM),” which ILO launched in December 2021 in Lebanon and aims to transition towards a formal economy and labor.

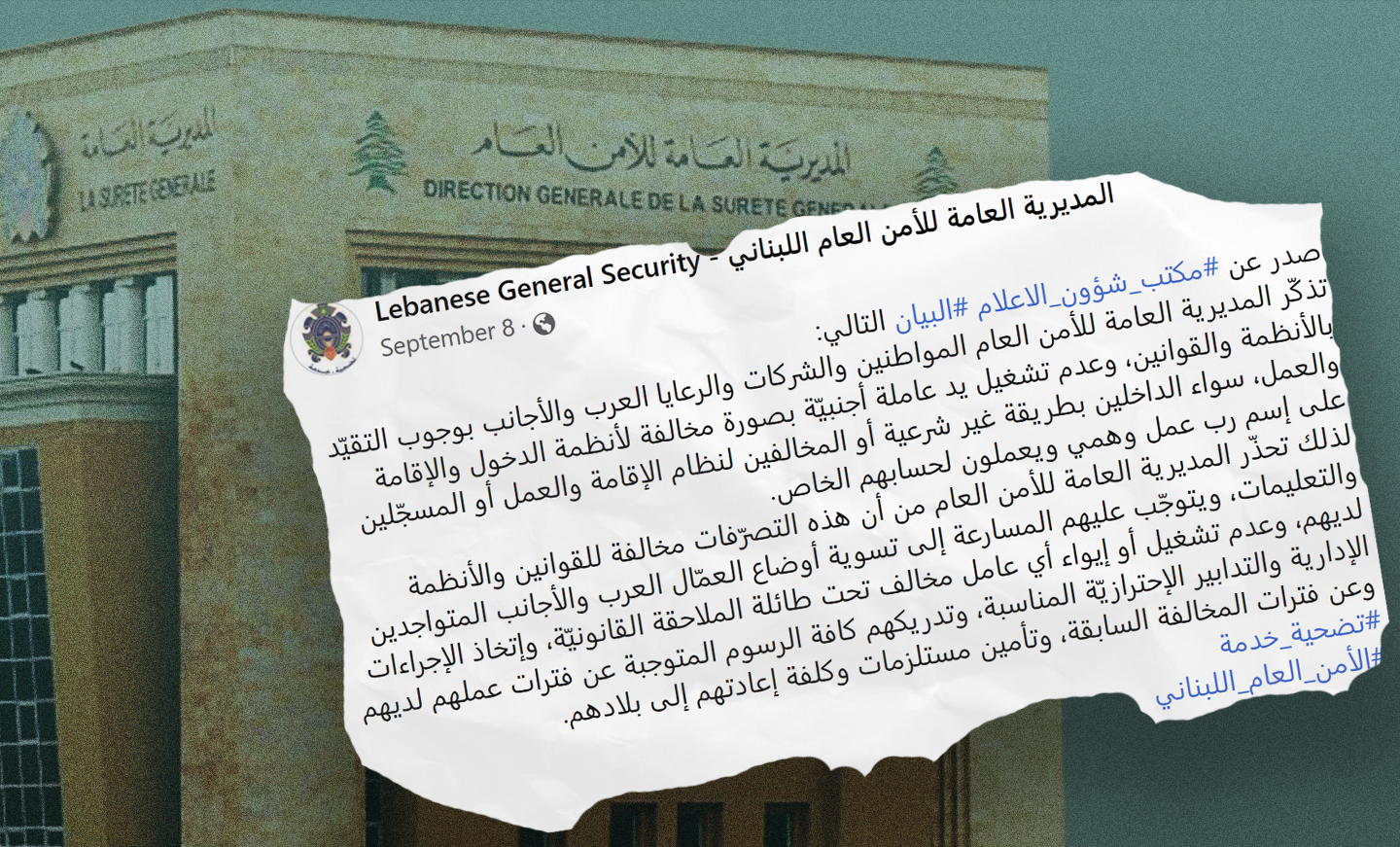

The General Security (GS) published a statement on September 8 warning employers about hiring “foreign workers via methods contrary to the entry, residency, and work laws.”

The warning included irregular workers, workers who entered “illegally,” as well as workers who are sponsored by a “fake sponsor.”

The GS advised employers against these practices, urging them to regularize the status of their non-Lebanese employees, stating that failure to do so is subject to penalty.

Synaps Academy, a collective of Syrian and European academics, published a research project on the reality of Syrian workers in Lebanon and the challenges they face in their daily work.

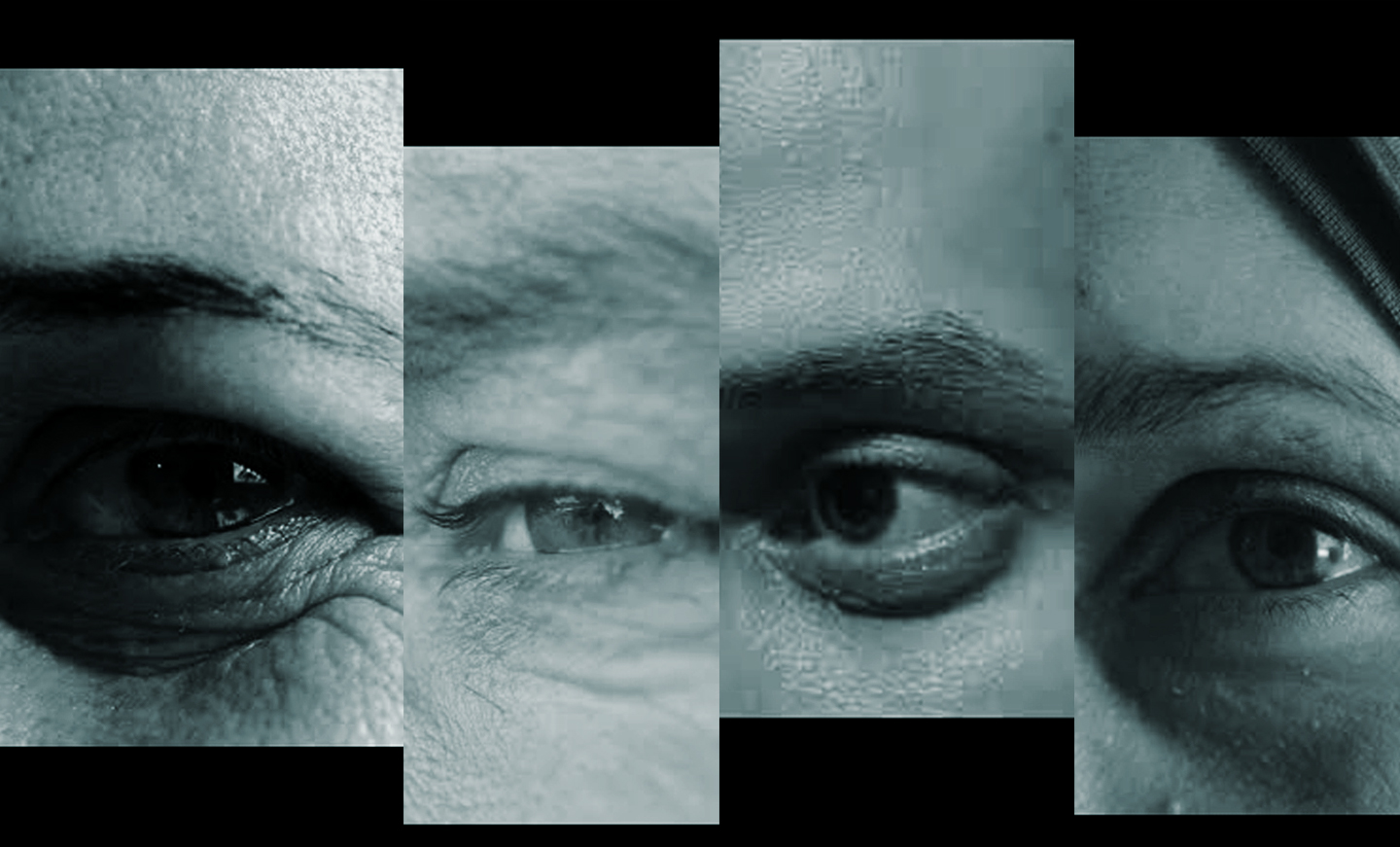

The project included a research essay titled “Lebanon’s Syrian Dilemma” and a series of 4 short documentaries following 4 Syrian workers from different backgrounds and industries (agriculture, sewing, construction, and repair).

The project emphasizes an often-neglected fact: a significant number of Syrian workers in Lebanon are ones who have entered and exited Lebanon for seasonal jobs since the 90s, and played an essential role in the reconstruction of post-war Lebanon.

The aim is to provide a more nuanced reading of the existence of Syrians in Lebanon, free of the typical racist discourse often presented in the media.

The project presents Syrians as an asset to the economic advancements in Lebanon over the past 30 years, as opposed to portraying them as a burden or a cause for the economic collapse, which is unfounded.

Migrant chef Anna Fernando presented a cooking workshop titled “Flavors Without Borders,” hosted by Nation Station and the Great Oven.

Fernando is a Srilankan chef who arrived in Lebanon over 30 years ago as a domestic worker. She later trained with a famous Lebanese chef, which allowed her to lead her own workshops.

“Each migrant has a talent, each one knows how to do something. I know how to cook. I like to show taste. Each migrant should show what they can do, in Lebanon especially.”

General Security Publishes List of Arrests, Entry/Exit, Work Visas Disaggregated by Nationality from Mid-July to Mid-August [here]

The General Security Office (GSO) published a breakdown of arrests, entry/exit, and work visas between mid-July and mid-August in the new issue of the GS journal released on September 10th. Highlights included the following:

- Nearly 412 migrants and refugees were arrested and interrogated;

- 417 migrants and refugees were released from detention after interrogation;

- Around 4,621 work visas were granted to migrant workers mostly from Ethiopia, Kenya, and the Bangladesh. There is no information on how many of these work permits were granted to newcomers.

454,813 foreigners and migrants entered Lebanon compared to 468,060 who left in the said time period.

Related Posts

Have Any Questions?

To inquire about this statement and the context, email us or fill the form.

Join Our Newsletter

At the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM), we are constantly working on a multitude of different activities and initiatives. Most of our activities are only possible with the help of dedicated and passionate volunteers who work in collaboration with our core team.

The Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) was launched in 2010 as a grassroots collective by young Lebanese feminist activists in collaboration with migrant workers and migrant domestic workers.

Quick Links

Useful Links

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Developed by CONCAT